In the wake of the January 2025 Los Angeles Wildfires we find ourselves talking a lot about ‘those impacted by the fires.’ But what does it really mean to be impacted? As of today, January 19th, there are 28 confirmed fatalities, 13 confirmed injuries, 1,963 damaged structures and 16,080 destroyed structures between the Palisades Fire and the Eaton Fire. We know that well over 200,000 Angelenos were evacuated during the wildfires. But what do these numbers mean? Certainly they are metrics that can quantitatively tell us that together, this wildfire storm is the second most destructive in California’s history and the third most deadly. But what lies beneath these numbers?

When looking at the activation of FEMA’s individual assistance program, the federal government examines several metrics including the number of structures destroyed. Certainly, the people who have lost their homes in these fires are the most severely impacted next to the families of those who lost their lives. But that is not the end of the story, particularly when fires rage through urban environments decimating entire communities.

What about the children who lost their schools and playgrounds to the fires? What about the business owners and patrons who lost their favorite restaurants, grocery stores or retail stores? What about the community members who lost their recreation centers, gyms, or libraries? What about the employees who will lose their jobs as a result of the fire—including laborers such as housekeepers, gardeners, and pool maintenance? Or the renters who will be given notice to vacate because their landlords lost their primary residence and now need to move into their rental property? Or the thousands of first responders who are working around the clock to contain the fires, keep our streets safe, restore power and water, provide shelter, relief and resources to the evacuees?

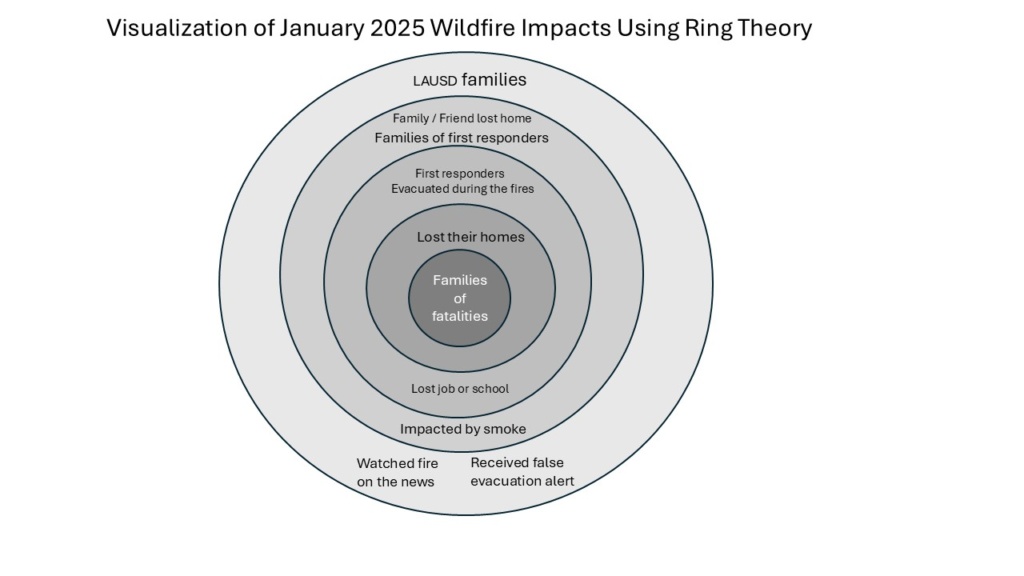

I would argue that all of the above are impacted by the fires, even if they may not be considered survivors by the metrics. As I wrote about in 2021, we need to broaden the definition of disaster survivors. However, it does not end there. If we pan out we can see that another layer exists—what about the friends and families members of those who lost their homes? What about the friends and family members who took in evacuees during the fires? What about the 500,000 LAUSD children who were kept home from school and their parents who missed work while the entire district closed for the fires? What about the families of the first responders—the children who keep asking why mommy or daddy doesn’t come home for dinner like they used to? What about those throughout the region, particularly those with respiratory conditions, who were forced to alter their routines to stay indoors to avoid toxic ash in the air?

It doesn’t take long to see that major disasters such as the LA wildfires are accompanied by a ripple effect. It is never easy to draw the line between who is impacted and who is not with a disaster of this scale. It has forever changed Los Angeles County and many of its 10 million residents. I believe that nearly all of Southern California is impacted by these fires—it’s just a matter of what shade of grey they fall into. When houses are burning live on local television at 12 o’clock in the afternoon with the firefight crippled by 100 mile per hour winds and when every cell phone in LA County receives a false alarm evacuation alert, wildfire permeates your psyche.

To bear witness to what our community has experienced this January takes its toll. I think that for many of us there is a reluctance to admit that we are impacted. We know that some people have had it much worse. Some people lost everything including their lives in these fires. Those of us who are impacted indirectly are thankful for our health, our families, our homes and our livelihoods. In many cases we don’t believe that we should count as impacted—we feel that donations, the discounts, and mental health support resources should be reserved for those experiencing the darkest shades of grey.

It’s Okay to Not Be Okay

I think it is important to acknowledge the affect of the wildfires and to not be too quick to dismiss the trauma that we have all witnessed. It’s okay to not be okay in times like these. It is okay to call the Employee Assistance Program, take a mental health day, or to seek out emotional and psychological support. At the very least give yourself grace—this was not the way that we wanted 2025 to begin. Don’t feel guilty for feeling sadness, feeling pain. Yes it’s true that others may have it worse but you are impacted too and it’s ok to acknowledge that. We are a community on edge right now—with a seemingly endless series of Red Flag Warnings on our horizon.

Use the Ring Theory to Give and Seek Support

The Ring Theory paradigm in psychology is used to visualize the ripple effect of a crisis with the most affected individual in the center surrounded by concentric rings with each layer gaining distance from the crisis. We can use this concept to visualize impacts of the LA wildfires and understand how to help. First identify which ring you fall into. As you grapple with your own impacts and trauma from the wildfires, remember to seek support from those who fall in the rings larger than your own but to provide comfort and solace to those who fall in the smaller rings. This will help to ensure that you can find support without placing a greater burden on those who are more heavily impacted than you.

Provide Mid & Long Term Support

In the early days of a disaster, the media focuses on the event nonstop. The spotlight is shone on the devastated community and an outpouring of physical and monetary donations are given. State and federal resources deploy to support the survivors. They are comforted in shelters, local assistance centers, disaster recovery centers and throughout the community at relief events. But after about 60 days, the world tends to move on. The wildfires will no longer be a daily story, many FEMA resources will be released, and the donations will diminish to a trickle. This is a very critical time for survivors as it is when the finality of the situation sinks in. Everyone else is moving on but they cannot. Recovery is a very long term process and they will begin to feel alone and disheartened. It’s at this time that some survivors will have a better understanding of their trajectory and what their true needs are. Continue to provide support to friends and family who are impacted by checking in, asking about their needs and donating to wildfire relief organizations during this critical time.

It will undoubtedly be a long and rocky road to recovery in the Palisades and Altadena. The most important thing we can do right now is to acknowledge our impacts, recognize where they fall in the rings, and to plan to be there for our fellow Angelenos in the long haul.