This disaster is nowhere near over, in fact I think things will continue to escalate in the United States for weeks. Yet the global pandemic of 2020, COVID-19, has already changed the field of emergency management forever.

Scale

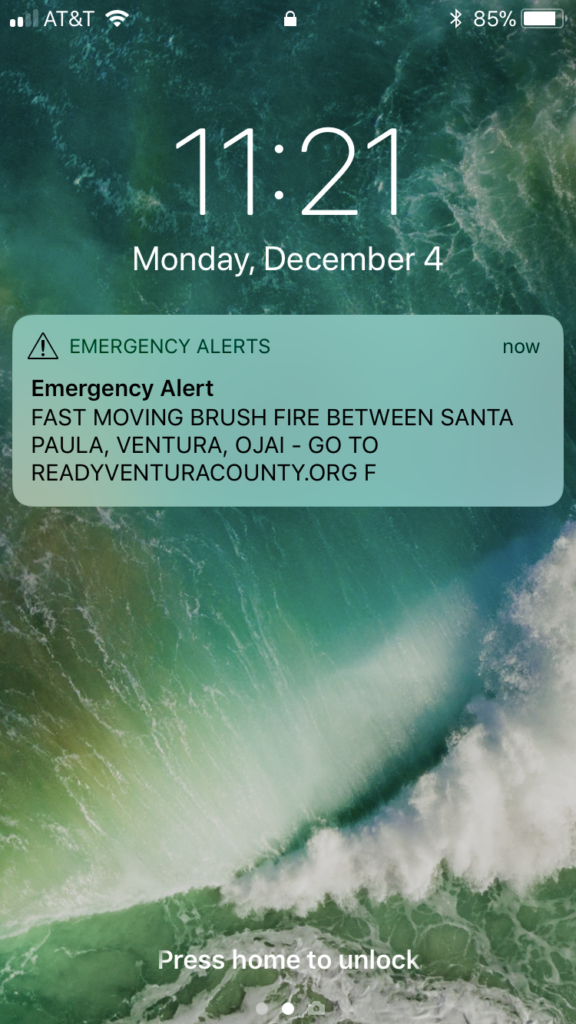

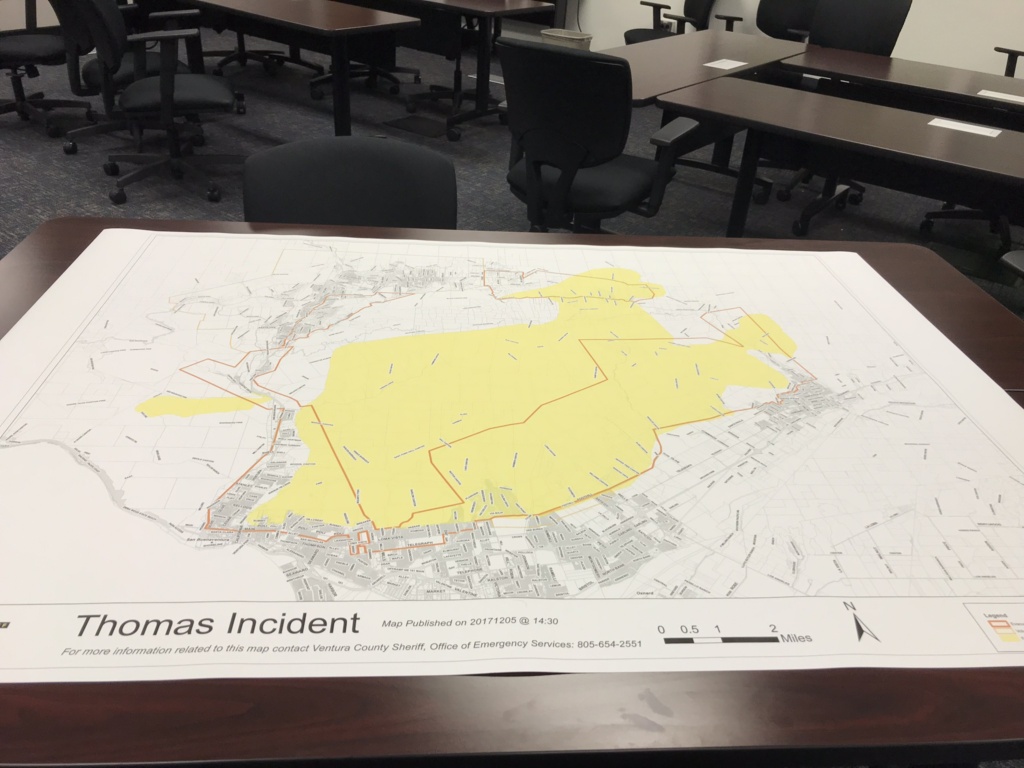

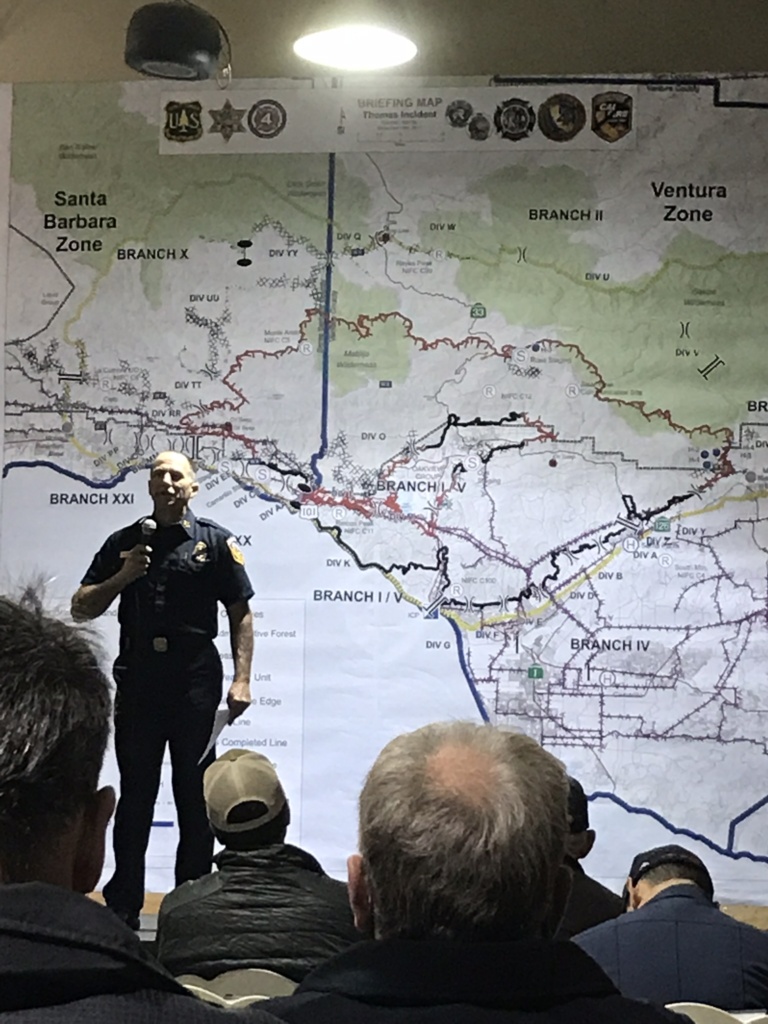

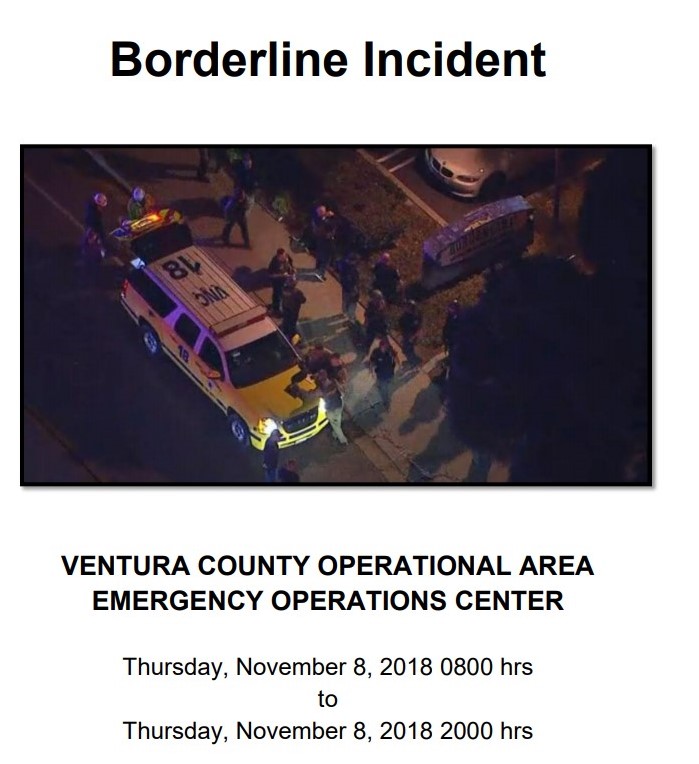

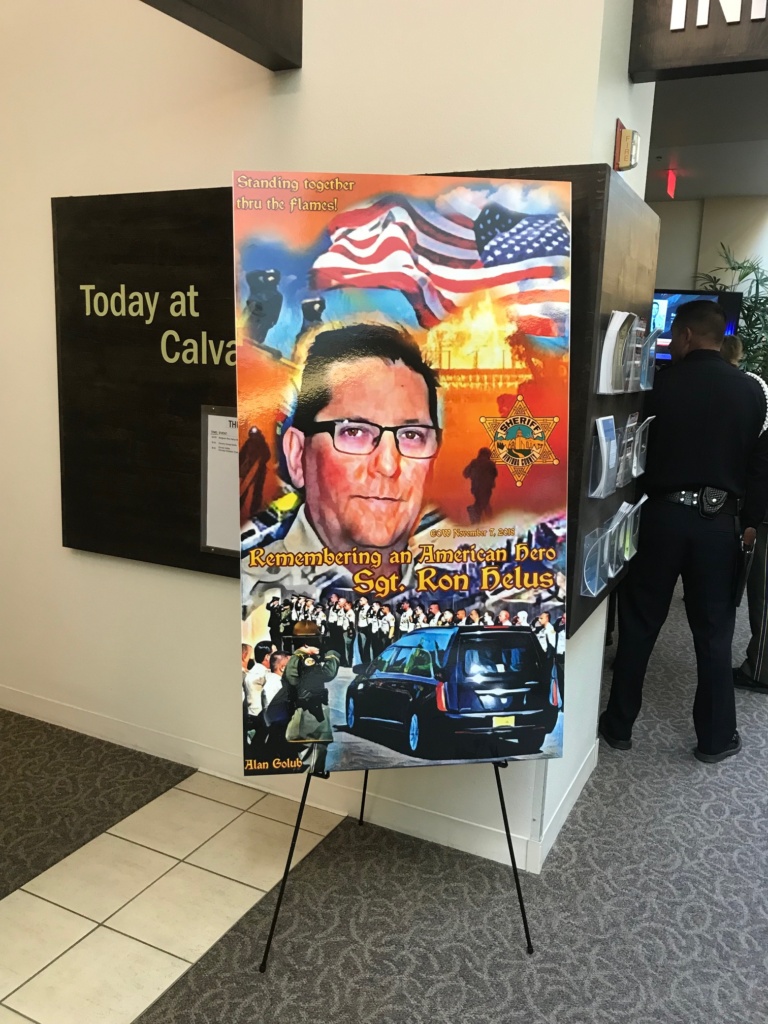

The word I keep finding myself using is unprecedented. I know we’ve said that before, to the devastation of the Camp Fire in 2018, the colossal losses in the Carribean when two category five hurricanes hit within 10 days, the drain on resources in Ventura County when a mass shooting occurred within hours of two major wildfires breaking out, the destruction of the Tohoku earthquake and pan-Pacific tsunami…all of these were catastrophic, for the jurisdictions they impacted. But none of these were global disasters. They were all regional. In California, we are always planning for the Big One, we just recently put a ton of time and effort into developing a Catastrophic Earthquake Plan for Southern California. It was always seen as this extreme scenario that would truly test our limits. But even in that seemingly extreme scenario there would be outside resources available, we could activate mutual aid systems and rely on our neighboring states, or at least the East Coast to alleviate some of our burden. If people wanted to escape the devastated region, they could migrate to other parts of the country as we saw with the diaspora following Hurricane Katrina.

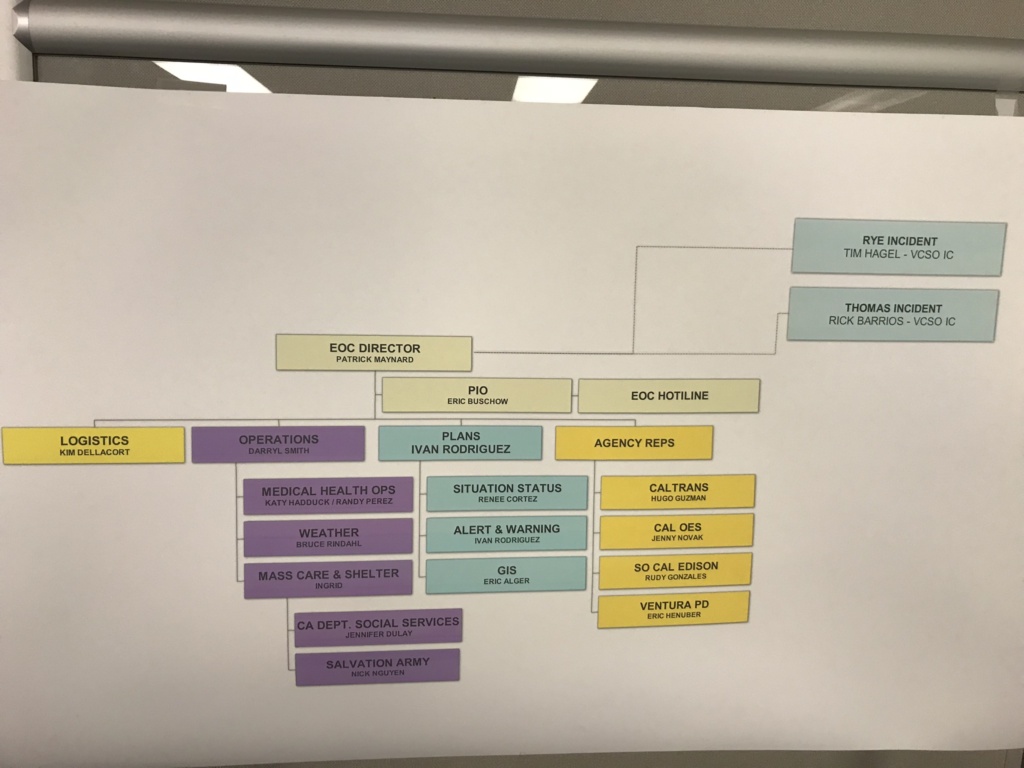

The pandemic is different. You cannot escape it, because you don’t know exactly where it is. You have to assume that it is literally everywhere in the world. Every jurisdiction is impacted. Everyone is proclaiming an emergency and everyone is activating their EOC (as of this morning there were 106 EOC’s activated in Southern California). The scale is just enormous, and I don’t think that it’s something that the state or the federal government ever really thought through or anticipated to the degree that we are now impacted. As it turns out when everyone everywhere is impacted a lot of the assumptions we have always made about emergency management change. How can the federal government possibly reimburse every jurisdiction? How can we make and distribute tens of millions of masks, gloves and other supplies everywhere simultaneously? Can FEMA and the American Red Cross be everywhere at once? Neighbors can’t help neighbors if everyone is impacted and if getting too close to each other puts our lives at risk. As we move forward from COVID-19 I anticipate a new subset of this field focused solely on global disasters, and not in the distant mythical kind of approach that we always used when talking about ‘megadisasters’ before.

Response Experience

The pandemic will be a great equalizer in a way because now every emergency manager who was working in 2020 has response experience. Obviously everyone’s role is a little different right now, but in some way literally all of us are having to respond or adapt our planning because of COVID-19. There are many emergency managers for small jurisdictions who might have NEVER had to activate their EOC in the twenty years they were working there. There are cities I have never even heard of in Southern California that now have activated EOCs. Some of us that activate regularly are getting a whole new kind of experience–one where there are real resource requests that need to be filled ASAP and LOTS of them. There are true shortages of supplies in this incident and we are all using that system for real now, not just talking about it in an exercise scenario. No matter what type of jurisdiction or what your role is, if you are an emergency manager in 2020 you have now earned your pandemic response badge. This response will be the topic of discussion and dissection for many years to come, everyone will have a story to tell and every jurisdiction is learning how to better operate their EOC’s after this incident.

Safety in the EOC

In most responses that I’ve been a part of, the Safety Officer position in the EOC typically became an ‘other duty as assigned’ because there was just not enough to do. This position makes a lot of sense in the field, at the ICP for a shooting or a wildfire, but EOC’s are pretty inherently safe working environments. Most of them are secured facilities that are built to withstand earthquakes, hurricanes, car bombs, etc. When non-EM friends see my posts about responding to fires, they typically say ‘stay safe’ without realizing that when I respond to an EOC I’m responding to an office like environment. I’ve joked many times that the biggest hazard for me is the 10 pounds I’ll inevitably gain from sitting too much and snacking on EOC food all day. But in this incident, all of the sudden our jobs did become dangerous. The Safety Officer is now critical in protecting EOC staff from spreading the virus–implementing medical screenings, keeping a strict sanitation schedule and ensuring work spaces are 6 feet apart are enough to keep any one person busy all day. Things we normally don’t think about like sharing a common pen with the sign in sheet, or using a common key pad to access a facility…all of these practices have now become hazardous.

It is also distressing in a way that many of us aren’t used to. If you came into this field having studied it and are passionate about operating at a coordination level separate from the field operations, this is probably the first time your job has truly been dangerous. We are not first responders, like firefighters and police officers. We aren’t used to putting our lives and our family’s safety on the line by going to work and now many of us are. I know several EOC’s that don’t have the space to practice social distancing–cramming 50-100 bodies into a small room and spending 12+ hours there. In the future, this is going to become a huge consideration for how we can better protect ourselves. I also think some of us may have a lot to chew on mentally–myself included–about whether we want to work in a job that can be so dangerous.

Remote EOC’s

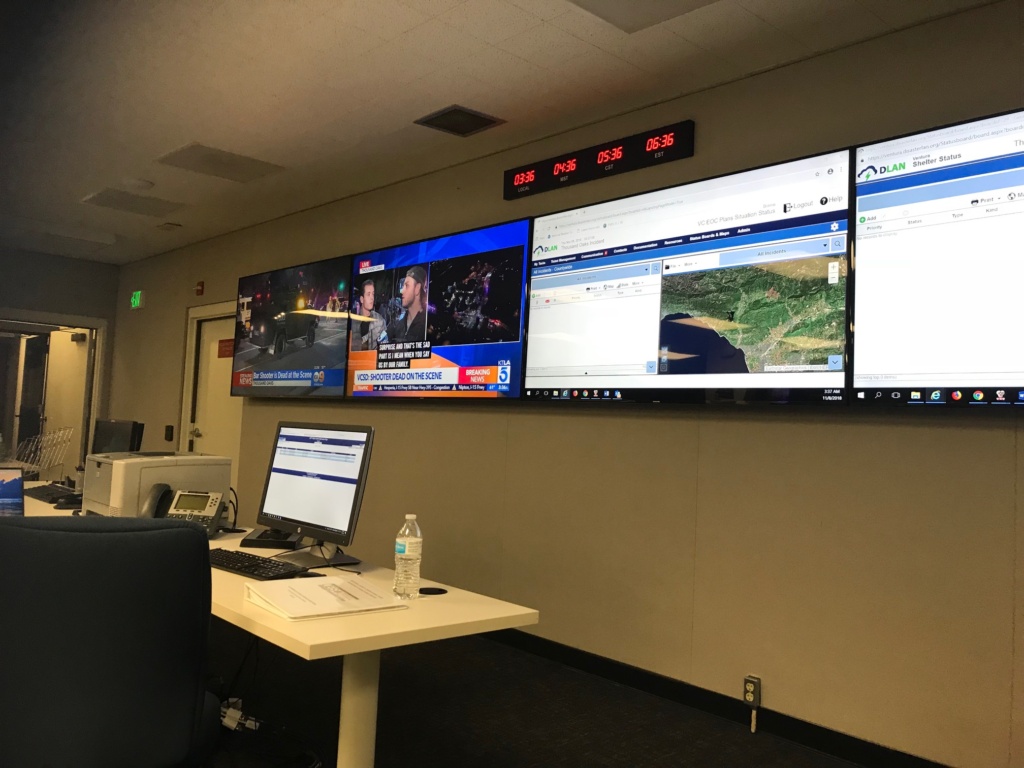

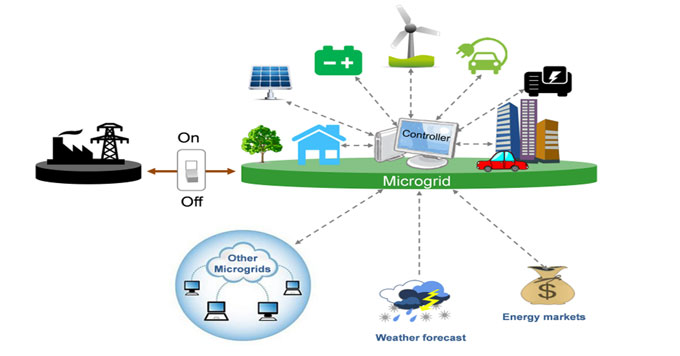

The discussion of safety in the EOC leads me to my next point. Most of us aren’t well equipped enough in our processes and procedures to take our operations virtual at this point. Some of our essential functions are still done with pen and paper, or with T-cards, or with hard copy 214’s, or with a desktop computer that has to be hooked up to a certain server. Many are scrambling right now to be able to execute the essential functions of their EOC’s remotely so as to preserve the safety of their critical staff. The tools are out there and some jurisdictions are extremely successful at this. Your planning meetings can be conducted over web conferencing, even press conferences can be as we are seeing in California. Email and phone allow you to ask questions of other sections. Virtual environments like slack that are conducive to group chats and discussion threads are extremely useful to engage several people working on the same problems. I think many of us have drastically underutilized WebEOC, VEOCI, and other EOC management software. It hasn’t been trained and integrated enough into our operation to be able to function at its full capability. I think this is a huge lesson learned from COVID-19. The ability to work remotely is crucial, and it is possible, we just need to practice and equip our responders to be able to do it comfortably. Pandemics aren’t the only disasters this can be good for, if roads are damaged in a major earthquake but communications are still up it might be a lot easier to get your EOC up and running virtually for the first operational period. This is the major way that I think this disaster will change the field.

Political Ubiquity

Now that every jurisdiction has been involved in such a major disaster response, all of our elected leaders are getting a crash course in disaster management. Whether they were engaged with EM before or not, they now undoubtedly have had to function in a crisis environment. More proclamations means that every city council and board of supervisors out there has had to draft and approve a resolution pertaining to an emergency. I bet it was the first time many of them had done it in decades. Mayors, governors, and even our President are giving press conferences on this disaster daily and having to learn good risk communication. They are learning a lot about continuity of government and just what services are essential. They are having to make some pretty big decisions that impact their constituents in huge ways–shelter in place orders? Closing down local businesses? These are not things that are easy to do and certainly won’t please all the voters. But as emergency managers I think that this is a win for us because I don’t think we’re going to have trouble convincing our bosses in the future why emergency management is important. For the next several years this disaster will be fresh in everyone’s memories on a scale we’ve never seen before. We are used to seeing news of distant disasters and being entranced for a couple weeks, sending donations and creating hashtags #anyplacestrong. But now that our lives are truly disrupted in a major way for an extended period, politicians and previously detached coworkers are going to care about our field.

More Funding?

That brings me to my last point, more funding. I have it with a question mark because in the immediate future I think a pretty big recession is inevitable, so I don’t think there is going to be much money to go around. However, I can tell you one thing. Emergency management programs are certainly not going to be the first on the chopping block as they historically have been in some jurisdictions. Executives will remember the plan, the program, the person they had to turn to in this dark time for guidance and they will not cut that program. I think that the long term fiscal impact on EM funding is going to be positive after COVID-19. I think there will be more emergency management positions created and hopefully more young folks interested in filling them. For once, everyone is going to see our value because this will be an incident that is not soon forgotten.

I am sure there will be many more lessons learned in the weeks to come of this prolonged disaster. But these are the initial ways in which I think our field will never be the same.