Recovery remains the murkiest phase of the disaster cycle. Unless you have experienced a significant disaster in your jurisdiction then you haven’t had an opportunity to practice and explore recovery concepts. Recovery does not have a well-defined beginning and end, therefore we tend to shy away from it and choose to focus our planning instead on the distinctive and adrenaline filled response phase.

US Federal Government Disaster Assistance

FEMA has two primary recovery programs that provide disaster assistance: Public Assistance (for local and state governments) and Individual Assistance (for individuals / households). The first step in accessing these programs is a request from the Governor to the President to declare a Major Disaster. Once received, FEMA will review information about the disaster’s impacts.

The metrics they typically rely on include the estimated monetary value to public property (obtained through initial damage estimates submitted by the local jurisdiction), the number of private housing units that are damaged or destroyed and the number of these which are uninsured. Based on these numeric estimates, and the Preliminary Damage Assessment validation process, FEMA will make a recommendation to the President about granting a disaster declaration and which types of assistance should be activated. Sometimes, only one type of assistance will be granted initially, and then additional categories will get added as more information is collected and verified.

Broadening the Definition of Disaster Survivors

This view of recovery is narrow, focused only on numbers and physical damages. As I outlined in my recent article on the ripple effect of disasters, the true impacts of disaster tend to be much broader. These include interruption to work and loss of hourly wages, losses experienced by undocumented populations, loss of outbuildings that were used for primary residences, displacement of renters outside of the disaster zone, school closures and childcare impacts, health impacts related to poor air quality, economic impacts due to air quality related closures, and psychological impacts on the greater community.

When we begin to think about the true number of people who could be defined as disaster survivors, we see that the reach is much broader than who qualifies for FEMA’s Individual and Household Assistance program currently. Assuming that you live in a county that was included in a Major Disaster Declaration for which Individual Assistance was activated, you have to be able to prove that you lived in a disaster damaged residential structure, prove that you were uninsured or underinsured, and show evidence that a member of your household is a “US citizen, non-citizen national or qualified alien.”

As depicted in a recent NPR article on FEMA’s high denial rate for disaster assistance applications during the 2020 Oregon Wildfires, this is not an easy process. “During last year’s fire season in Oregon, FEMA didn’t approve roughly 70% of claims. That’s after FEMA filtered out applications it had deemed as potentially fraudulent. In California, FEMA didn’t approve 86% of claims.”

There is much room for error in the paperwork process and if the automated systems are unable to verify you along the way, your application will likely be denied. Of course, there is an appeal process but many who see the word ‘denied’ simply move on. Hassling with bureaucratic paperwork and jumping through hoops is the last thing that most disaster survivors want to do.

So if those who meet the currently narrow definition of survivors are experiencing their share of problems accessing aid, how do we go about creating a system that supports an expanded definition of disaster survivors?

Involving Community Based Organizations

While government financial assistance can be extremely beneficial, it shouldn’t be relied upon as the only way to support individuals following disasters. That’s where non-profit organizations and community based organizations can step in to be incredibly important local assets. Case management efforts can be best coordinated by the formation of a Long Term Recovery Group (LTRG) for resource and information sharing. Following the series of disasters in 2017 and 2018 in Ventura County, the LTRG became a critical driver of recovery efforts. The group ensured that monetary grants provided by the American Red Cross, Tzu Chi, the Salvation Army and others were issued in a coordinated manner and helped survivors navigate the process of identifying and applying for all available aid.

One of the leading organizations in Ventura’s LTRG is the Ventura Community Foundation. Before my experience with the recovery, I was unaware of the role that such foundations can play after disaster. According to the Council on Foundations,

“Community foundations are grantmaking public charities that are dedicated to improving the lives of people in a defined local geographic area. They bring together the financial resources of individuals, families and businesses to support effective nonprofits in their communities.”

As a trusted fiduciary agent in the community, the Ventura Community Foundation has been able to provide both short and long term recovery grants to individuals and community based organizations impacted by disaster and also partner with grassroots organizations to amplify fundraising and giving efforts. This is a largely untapped resource for emergency managers, and a critical stakeholder to identify and bring to the table in pre-planning efforts. The mission of such organizations aligns closely with filling the gap between survivor needs and available assistance.

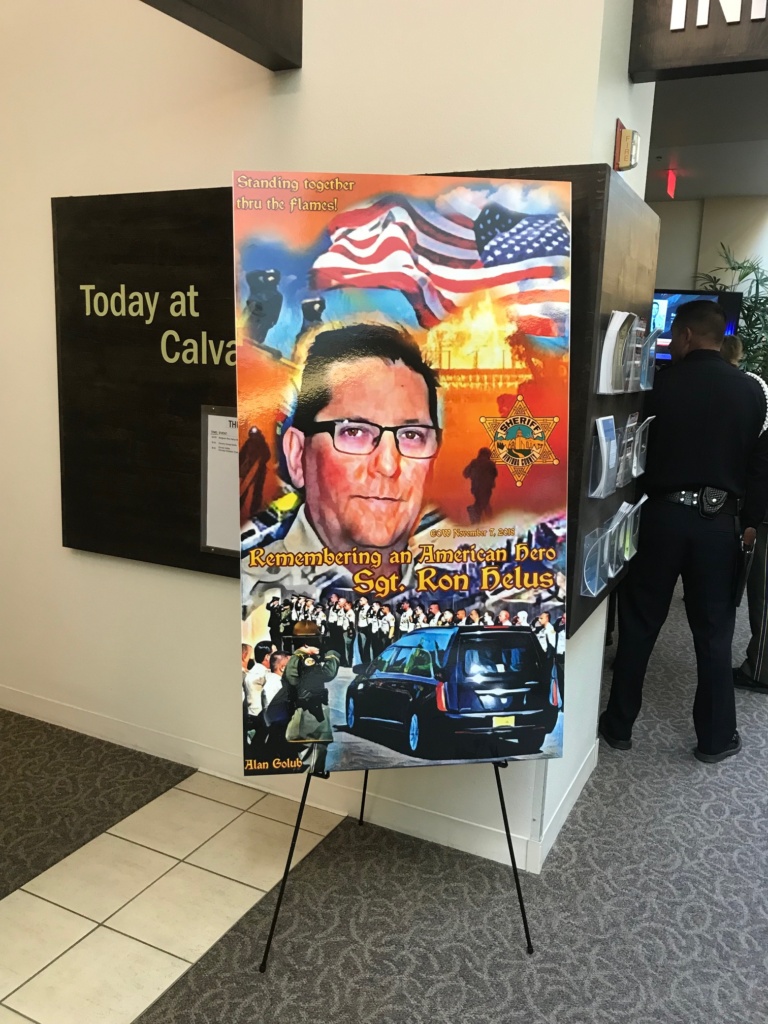

Shift the Focus to Community

My experience and research on recovery has revealed that an effective recovery strategy is to expand our focus from individuals to the community. While financially supporting the most deeply impacted individuals is a critical component of recovery, there are many non-financial factors that can support survivor recovery too. One is having the ability to share their story, which is most effectively done through community healing events, such as fundraisers, vigils, and memorials that specifically recognize the hurt and trauma that disaster has caused. Effective case management staff, volunteers, emergency managers and any other representatives working with the survivors can also help meet this need simply by allowing space and time for survivors to share their experiences. It may take an extra hour out of a busy day, but as architects of community recovery we need to recognize and understand this need and build time into our agendas to allow it.

Another key factor in survivor recovery and post traumatic growth is feeling connected to something greater than themselves. Service opportunities allow survivors to give back and regain their agency, thus rewriting the narrative that might have painted them as ‘victims.’ Creating such opportunities alongside community events can be a huge booster in community resiliency and recovery. As much as possible, survivors need to find a place and mechanism to connect with one another, to hear each other, and to console each other. Local businesses and organizations can be huge assets in facilitating these opportunities.

New Methods of Measuring Recovery

When I gave my recovery presentation at the IAEM Encore conference last month, I was asked a really interesting question: If acres burned and homes destroyed don’t tell us the full story, what metrics should we be using to measure recovery? As I’ve considered this question, some immediate ideas drawn from the ripple effect come to mind. Perhaps we can look at economic statistics—jobs lost, hours lost (although how do you gather that data?), retail losses, tourism losses, agriculture losses, etc. And maybe we could measure through days that schools and other anchor community establishments are closed. Another possible metric could be the number of people seeking assistance through local non-profits. In Ventura County, a good indicator was the number of disaster related calls placed to their local 2-1-1 (help line for general questions on services, resources, and information in the county).

But the more I thought about the question, the more I realized that trying to find a quantitative method to measure recovery might be the wrong approach. Instead, maybe we need to try to measure it qualitatively. Numbers can only tell us so much. Metrics cannot convey the true human impact of disaster the way that survivor stories can.

To really illustrate true impacts, relief agencies need to understand what it was like to be there during the disaster and the lingering social, psychological, and economic impacts that survivors feel. Focusing on the direct financial impacts will only ever tell a sliver of the story. Let’s look instead toward ways to collect qualitative data—what are the themes of loss, hope and healing among survivor stories?

At the beginning of 2020, Ventura Community Foundation held a ‘Ted Talks’ style event where disaster grant recipients shared brief stories about the impact of the funds on their recovery. It was emotionally moving and hugely successful– benefactors left with a much deeper understanding of where their dollars were going and a strong motivation to continue giving. When survivor stories are published in media, they can also reveal losses and plight of the more ‘invisible’ members of the community.

Expanding Emergency Management

In the recovery phase there is a fine line between making life better for disaster survivors and making life better in general. Often, disaster serves to illuminate pre-existing inequities and inadequacies in social systems. It’s hard to isolate needs that are related solely to the disaster and turn a blind eye to needs that also exist in blue skies. That is where recovery so closely blends into the mitigation phase of the cycle–what can we design, develop, and build back better so that the next incident doesn’t become a disaster?

This nexus between recovery and mitigation is the most fascinating to me personally, and the area where I think that our field has the most potential for growth. Here is the place where we can really show our value and embed our work with community development, economic development, urban planning, social advocacy, environmental justice, and other agencies who work on reducing social vulnerability every day. These may not be the first stakeholders we imagine when we think about whole community partnerships, but they are unequivocally important to engage during recovery. And as we all know, it’s better to build the relationships before the disaster hits.