Earlier this month I gave a presentation, Dynamics of Recovery: Navigating the Long Haul at the International Association of Emergency Managers Encore Conference. This was the first time the professional association had done a mid-year two-day virtual summit featuring follow up presentations by select speakers from last year’s conference. (You can view my 2020 presentation on Navigating the Transition from Response to Recovery here—it will be a few more months before I can release this month’s presentation.)

I was excited for the opportunity to expand on recovery after all the research I’ve been doing for my Ruin to Rebirth book project and the trends I’ve been seeing after recent disasters in California. One of the things I chose to focus on in this presentation was how we really need to broaden the definition of disaster survivors. When it comes to determining eligibility for disaster aid, FEMA tends to rely heavily on statistics of damaged / destroyed homes and the percentage of uninsured losses in a community. The need for simple metrics is understandable when you must make comparisons between communities to determine the areas of greatest need. However, this approach is a drastic oversimplification of the impact disasters have on communities. In this article I will discuss the ripple effect of California’s wildfires as background for an upcoming article on new ideas for measuring recovery and how we can broaden the definition of disaster survivors.

Smoke’s Influence on Air Quality

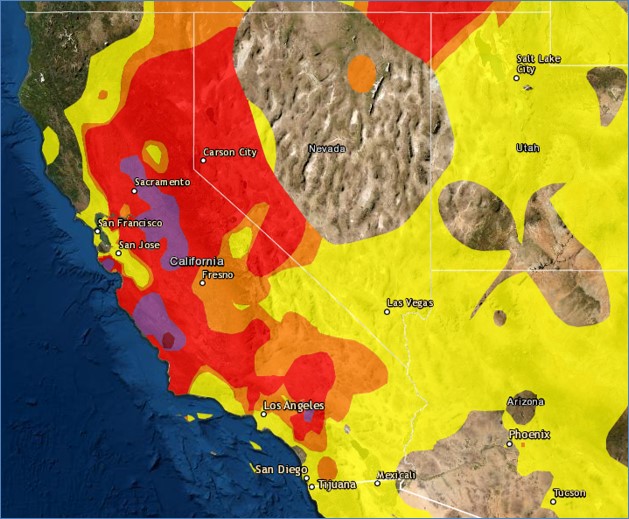

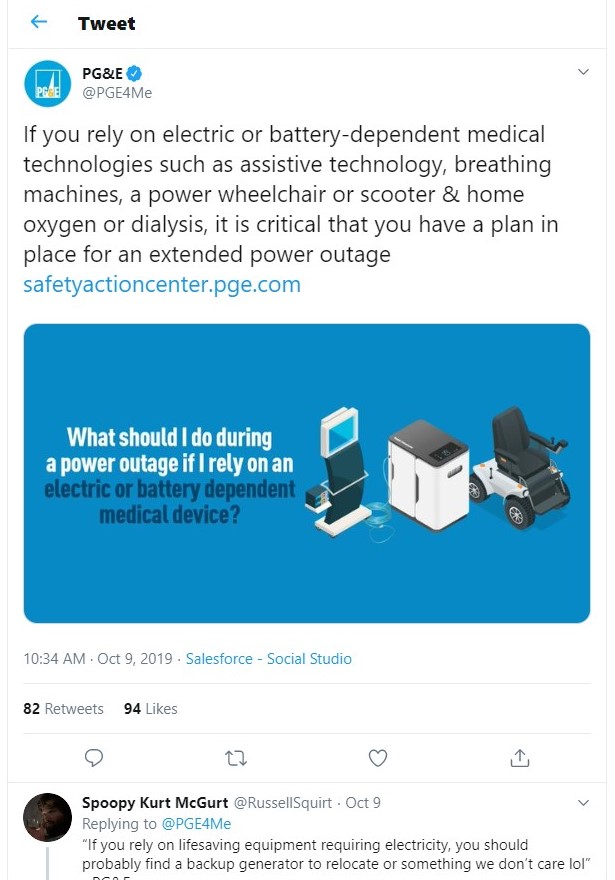

When discussing wildfires, the influence of smoke on air quality is a key issue that drives disaster impacts way beyond the burn area. While the direct physical impacts of flames are limited even in large fires, smoke quickly becomes a regional or even statewide affair. In California’s 2020 wildfires air quality impacts were observed hundreds of miles from the burn areas for nearly an entire month. When air quality is poor it ignites a domino effect of negative consequences for industries—prompting closures at schools, outdoor retail, recreation, and tourism, and placing severe limitations on agriculture, construction, and landscaping.

Poor air quality has also been linked to dire health impacts. During widespread smoke incidents, both emergency room visits and deaths of elderly people increase dramatically. While the official fatality count for the 2020 wildfires is 26, a Stanford study estimates that this number could be up to 50 times higher—up to 3,000–when smoke impacts are factored into the equation. “These are hidden deaths. These are people who were probably already sick but for whom air pollution made them even sicker,” Marshall Burke, Deputy Director of Stanford’s Center on Food Security and the Environment told the San Jose Mercury News.

With chronic respiratory disease such as asthma on the rise in recent years, likely due to ambient air pollution, this is especially troubling for the health consequences that prolonged and frequent wildfires could have on younger populations too. The 2020 wildfires also coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic, meaning that there was an even greater vulnerable population with compromised respiratory systems due to the disease.

2017 Thomas Fire: Economic Impacts

As you might remember from previous articles, I was heavily involved in the response and recovery to the Thomas Fire in Ventura County through my role with CalOES. So I’d like to share some impacts that the Thomas Fire had on Ventura County to illustrate how deeply the community was disrupted beyond the modest 1,000 or so homes that were lost. These social and economic impacts begin to help us understand the magnitude of the ripple throughout the community, much of it instigated by smoke.

The Thomas Fire began on December 4th, the height of the holiday shopping season for many of Ventura’s small retail businesses. In Southern California’s ideal coastal climate, many businesses are located in outdoor shopping malls that were forced to close due to poor air quality during a critical time period in the shopping season. It was estimated that retailers in the impacted and adjacent areas would lose 20% of their annual revenue for 2017 and continue to feel losses into 2018 due to the fire.

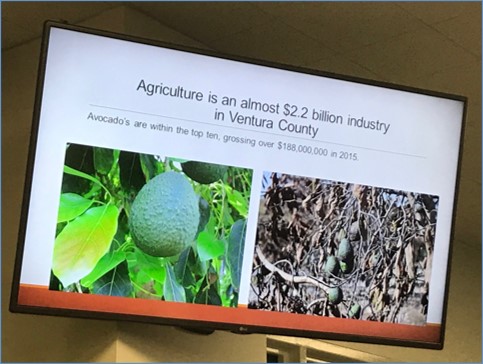

Agriculture makes up a large percentage of Ventura’s local economy. As smoke permeated the valleys below the flame engulfed mountains, it was unsafe for outdoor farmwork to continue and many of the community’s most vulnerable were out of work during the holiday season. No workers meant no crops and thus agriculture suffered too. Crops were also directly impacted by the heat of the fire. Avocados are one of the top 10 agricultural exports in Ventura’s $2.2 billion dollar industry. The 2017 yield for avocados was decimated by the fire. But the impacts of the high heat were not limited to the current fruits, as it also caused a massive die off of the avocado trees, which would destroy business for years to come.

Tourism is another major industry in Ventura county. The picturesque location linking the Pacific Ocean with agricultural plains and oak covered hillsides makes for a perfect getaway backdrop. The Ojai Valley is reliant on tourism with about 31% of all jobs in that industry. Nestled in the rolling hills it is an ideal spot for retreats–for both business and pleasure. The Thomas Fire caused the Ojai Valley Inn, one of the major employers and economic drivers for the community, to close for two weeks as most of the Ojai Valley was evacuated when it was entirely surrounded by fire. Smaller hotels and businesses in Ojai were also closed. These closures caused many hospitality employees to lose hours or suffer unpaid weeks off during a time when most were reliant on their paychecks to give their families a good holiday season.

In all three of these industries, the majority of workers are hourly. Due to the uncertainty of the crisis, most employers were simply reducing hours rather than laying workers off, thus the true impact on jobs remains unknown since it is not reflected in unemployment data. This also made it difficult for workers to plan financially or access unemployment benefits since they were not technically unemployed.

School Closures

Due to air quality issues in the Thomas Fire, most of the schools in Eastern Ventura County were closed for two weeks in December prior to their holiday break. As the nation has seen during the COVID-19 crisis, school closures have massive ripple effects in a community. When children are out of school, many parents are forced to stay home from work–often in sectors that are not well equipped for telework or in industries where they do not have sick or vacation time benefits to use. This puts additional financial strain and mental stress on families who are forced to adapt to a lifestyle where everyone is at home and parents are unable to earn income or work productively. Many low income families are also reliant on school lunches so school closures can increase hunger and food insecurity in the community.

During the 2020 wildfires, I was managing the California State University system’s response. Over the span of August to September, we had seven campuses close for at least one business day due to poor air quality. We also had at least 26 members of our CSU campus communities lose their homes due to the wildfire. Power outages, evacuations, and closures also influenced the ability of students and faculty to participate in online courses, which made up most of our academic offerings at the time due to the pandemic.

Displacement and Housing Impacts

Prior to the fire, Ventura had already been experiencing a housing crisis. Rates of homelessness were on the rise due to increasing rents and plummeting vacancy rates. Ventura County was in the top ten least affordable housing markets in the nation and only about a quarter of the County’s population could afford a median priced home. The vacancy rate in Ojai was less than one percent and Ventura’s was less than 2%. So even if you were in that lucky 25% who could afford to own a home, they were incredibly difficult to come by.

The fire only exacerbated the housing crisis in Ventura. While over 900 housing units were destroyed, the County knew unofficially that many of these units housed multiple families, sharing space to alleviate the high cost of rent. There were also over 200 outbuildings destroyed. Although FEMA would not count these as homes in the certified count, it was known that many of them were occupied by extremely low income farm workers. Since they were not technically residential units these people would not have access to many of the benefits that other disaster survivors would.

Another way that the housing market shifted after the fire was through the displacement of renters. While the fire itself destroyed many large beautiful homes in the hills, renters in Ventura city came to bear the burden of seeking new housing. This was because homeowners in the destroyed neighborhoods owned more than one property. So, when their primary residences were destroyed, these landlords relocated to their rental units while rebuilding their homes. This meant that renters who had been paying month to month were now given notice and had to join the incredibly difficult hunt for housing in Ventura. They were an entirely untrackable population who were deeply impacted by the fire, having lost their place of residence but would have no access to any survivor benefits and would simply be on their own to fight for housing.

Looking Forward

To really understand this dynamic, complex, and lengthy phase of the disaster cycle, we need to broaden our perspective and consider the far-reaching impacts of disaster on our communities. In my next article, I will discuss new ideas for measuring recovery that go beyond the simple metrics of acres burned and homes lost.