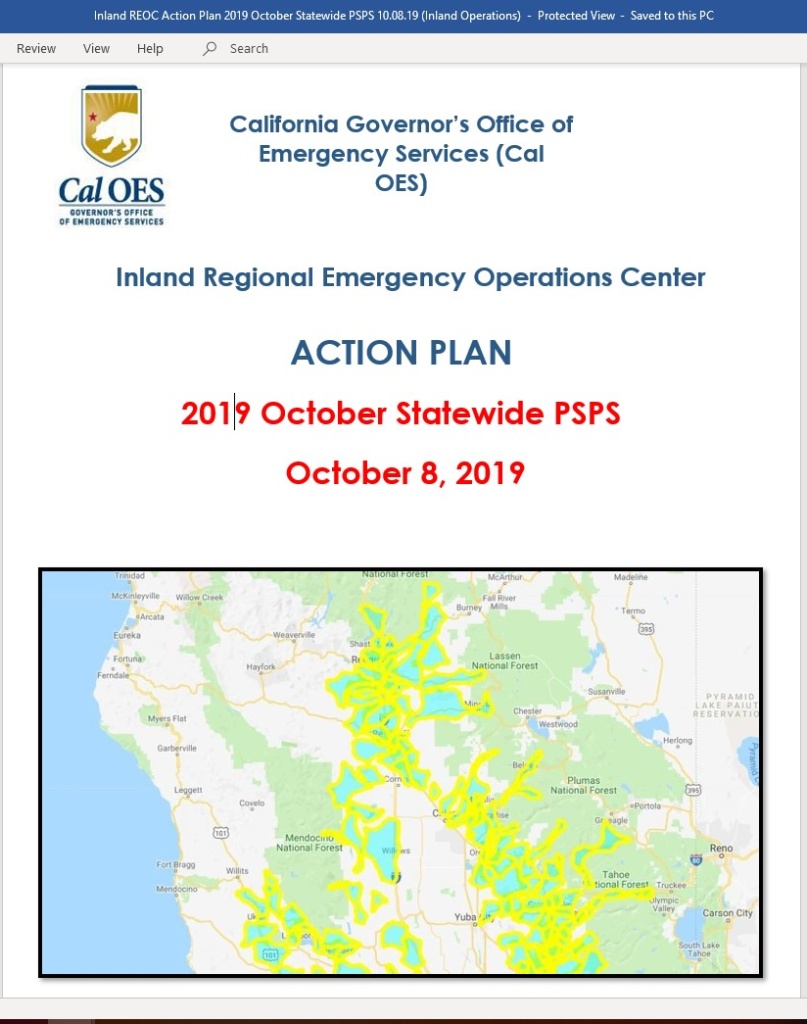

Last week, California experienced the largest Public Safety Power Shut Off (PSPS) to date when Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E), its largest investor owned utility cut power to approximately 738,000 customers in 35 counties. One of which was Humboldt County, where I grew up and still have many friends and family members, which lost power for 24 hours with one day’s notice. Another was Tuolumne County, where my sister-in-law and her family live, where customers were plunged into darkness for nearly 4 days. While I have been dealing with the new reality of PSPS as an emergency manager for more than a year, most people are only learning of the protocol and its significance this month as a result of the massive outage.

I wanted to take the opportunity while there is public attention on this issue to write an opinion piece on PSPS and its ramifications. While I am currently employed by the California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services (CalOES), I want to be clear that what I’ve written here is my individual opinion and does not represent the opinion of my employer. However, I do want to commend Governor Newsom on his letter earlier this week to the California Public Utilities Commission and echo some of his sentiments that the scope and duration of this PSPS was unacceptable and executed with astounding neglect and lack of preparation on behalf of PG&E.

What is PSPS?

Public Safety Power Shut Offs, or ‘PSPS’ as they are affectionately called in our industry, are a new tactic employed by investor owned power companies in California to proactively shut off power in specific areas during times of high wildfire risk. While San Diego Gas & Electric (SDG&E) has been practicing this for years, Southern California Edison and Pacific Gas & Electric have just started implementing PSPS in the last couple years, due mainly to the fall out from recent devastating fires in Sonoma, Butte and Ventura Counties that were determined to be started by electrical equipment. This allows the companies to play it safe when weather conditions are primed for wildfires and avoid potential future liability that could be incurred through wildfires caused by electrical equipment. They closely monitor the impending weather conditions utilizing their own staff meteorologists, then send field staff out to the most fire prone locations as the weather event commences. When localized weather equipment and field staff concur that dangerous conditions exist, they proactively shut off power to select circuits in vulnerable areas.

People generally aren’t too happy about this new protocol—it means that perfectly good groceries will rot in refrigerators and cranky Californians will fumble with flashlights in sweltering homes on the state’s hottest days. For what reason? Will this really stop wildfires from starting? Great questions, I’ll attempt to address this below. It’s important to note that although many people are seeing ‘CalOES mandated’ with some of the notifications on the power outage, CalOES does not mandate the power companies to turn off power. CalOES mandates that if they are going to do this, that they notify both customers and local governments in the affected areas in a timely manner.

Community Repercussions

The highly publicized widespread planned outages allowed us a view into the current level of California’s preparedness, and it didn’t look good. In Humboldt County, gas station lines were extremely lengthy until they transitioned into being eerily empty as many stations ran out of gas. Grocery stores were swarmed with crowds until the shelves were cleared of water, canned goods, toilet paper and other essentials. Some stores offered steep discounts on perishable refrigerated and frozen foods that were likely to be destroyed in the extended outage. There was a general sense of mayhem as people went into a frenzy trying to prepare for a few days without power. This shows us that in general, people didn’t feel that what they had at home was adequate to comfortably survive even a few days. This is not a good sign for being prepared for the Big One. Fortunately, it’s a great time for emergency managers to capitalize on this by encouraging participation in the Great ShakeOut earthquake drill later this week.

The upside to this is that people were forced to give disaster—or living in this alternate universe without power—their thoughts and attention. It is so common for people to push it out of their minds by saying they’ll prepare next month or that disaster won’t happen in their lifetimes. When they knew that the outage was impending, people considered their current commodities and took action. While a full tank of a gas or stash of canned goods will be fleeting, some of the items procured will have a lasting impact and will boost overall personal preparedness. Perhaps people will be more likely to purchase generators to mitigate the darkness of future outages. Thinking through the scenario and discussing it with family members is also going to pay dividends toward the creation of a family emergency plan, even if it’s conversational and focused mainly on power outages. Hopefully it can start the train of thought toward greater emergencies and what to do if gas or sewer systems are also not working. Maybe in the future, people will recall the long gas station lines and remember what a precious commodity fuel really is so they’ll keep their tanks at least half full so that emergencies won’t limit their mobility.

The outages had a big impact on small businesses that did not have generators. In Humboldt County most of these businesses were forced to close and lose revenue for the duration of the outage. Gas stations closed such as the Chevron in Eureka where my brother works and even the Safeway in Arcata where my mom works as a result of their generator malfunctioning. Excess product that needed refrigeration became waste and money was lost on these products. While corporations like Safeway and Chevron will be just fine, a PSPS event can wreak havoc on small businesses that are often teetering on the brink of profitability in rural areas such as Humboldt or Tuolumne.

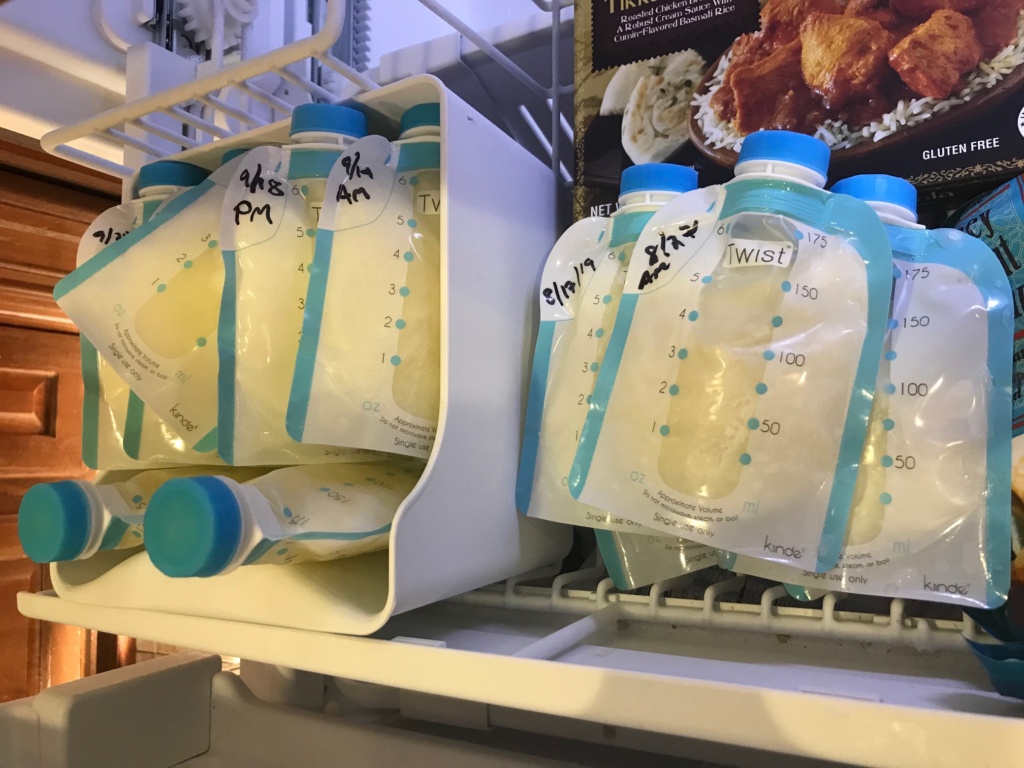

As with most disasters, populations with access and functional needs will be the hardest hit with PSPS. Lower income people who cannot afford to refill their freezers and refrigerators with food staples that they’ve been depending on were adversely impacted by this event. Hourly employees of shuttered businesses lost wages when they could no longer go into work. As a breastfeeding mother, I could be very impacted by an outage. I would be horrified to lose my supply of frozen milk that I have been building for months—it is literally priceless, produced by my own body for my infant and cannot be replaced.

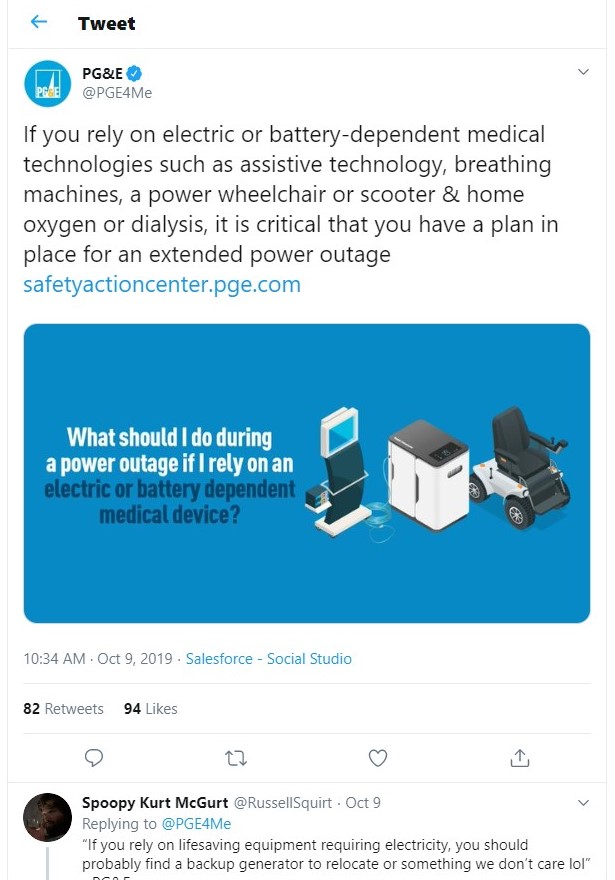

Perhaps the most important consideration of all for PSPS, is those who need electricity for medical reasons. This includes those dependent on oxygen, dialysis or CPAP machines, motorized mobility equipment or insulin that needs to be refrigerated. A power shut off can be catastrophic for people with these needs. PG&E was outspoken on social media during last week’s outage that these patients need to develop their own emergency plans and be prepared. Is this an acceptable stance to take when lives are at stake because a power company wants to reduce their own liability?

Impact on Emergency Management

For local emergency management agencies, PSPS means more planning calls and more Emergency Operations Center (EOC) activations in anticipation of possible emergencies rather than in response to real emergencies. While this can be great practice in activation protocols and running through the process for smaller jurisdictions that don’t get much action, it can also become a huge headache quickly. And it can present a level of danger—if staff are already tired from being activated for a forced power outage, does it make them more capable or less capable to respond swiftly and competently when real disaster strikes? I know that at the Regional level, activations for PSPS exhaust our resources quickly. CalOES deploys Emergency Services Coordinators to any activated counties and also to utility EOC’s. If a real wildfire emergency occurs and shifts need to be filled overnight and to staff our Regional EOC, then we quickly begin to run out of personnel resources and must rely on overtired staff who would’ve otherwise been refreshed and ready to go when the real fire ignited. I can personally testify to this happening in November 2018 when the Camp and Hill / Woolsey fires began as we had been in PSPS mode all week. Although I’m out on maternity leave, I have also heard that this was the case last week with the October 2019 Saddle Ridge fire. These types of activations will become more and more common, with Southern California Edison already moving into a constant state of EOC activation for every weekend through wildfire season in 2019.

The other drawback is that the capability of communicating important emergency evacuation information with the public can be greatly diminished if power is out. There are many ways for wildfires to ignite and cutting the power simply won’t mitigate all fire start potential. So if a fire starts a different way and begins to impact a community in the dark, how can emergency management quickly notify them? Television media won’t reach them and cell phones may have varying levels of battery power depending on outage duration and community access to generators. Sending first responders door to door is a very resource intensive option that can be slower than other methods. This presents a greater danger to these communities.

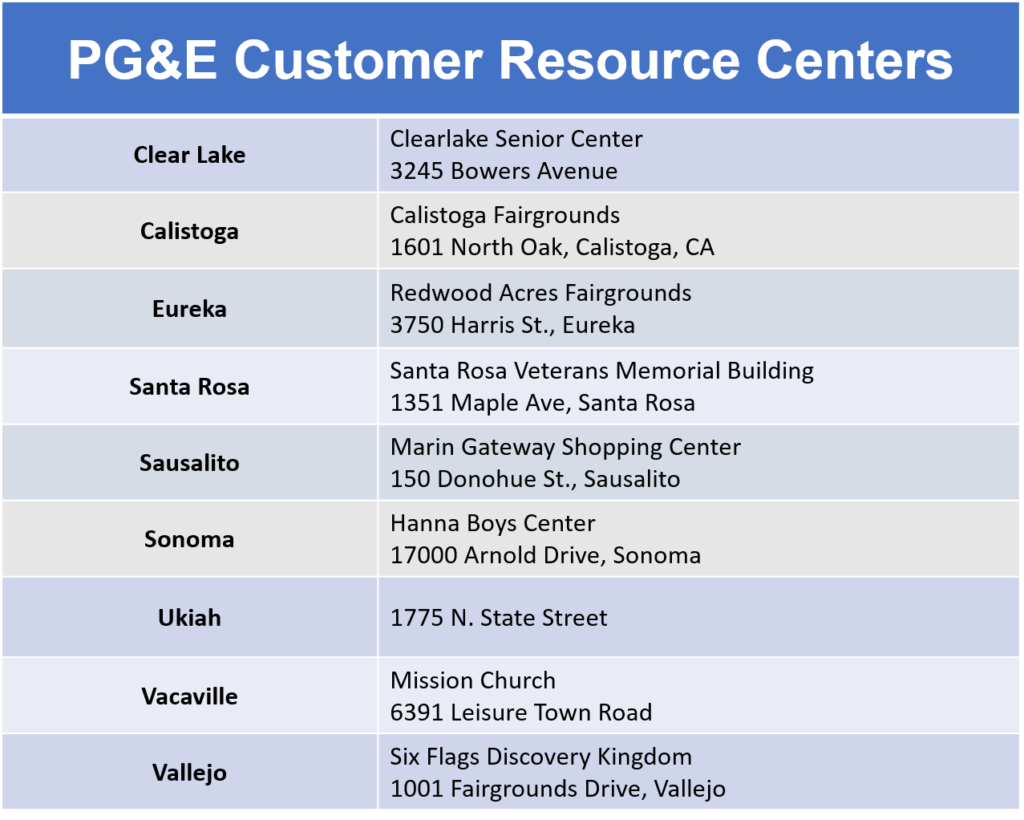

PG&E committed to opening one ‘Community Resource Center’ per county with a maximum of 100 people to provide device charging capabilities and controlled temperatures. While I appreciate the gesture, I find it almost laughable that these centers would even begin to meet needs. In many of the 35 impacted counties, it would be quite a drive for those most at risk in the more rural mountainous areas to the resource center in the more populous part of the county. In Humboldt County, the resource center opened hours after power had been restored for much of the county, with the exception of the distant rural areas. This quickly becomes a need that local emergency management becomes involved with by opening additional cooling centers or resource centers. These centers further stretch staff resources that would be needed as shelter workers if a wildfire hits.

As stewards of the whole community, local emergency managers must also plan for the needs of the medically vulnerable populations previously mentioned. Since many do not have the resources or knowledge to fully prepare themselves as PG&E suggests, emergency managers try to fill this gap by working with public health to identify and check on the well-being of these populations during outages. As you can imagine, this can quickly become an information management challenge and a losing battle as the number of people impacted increases.

Does it work?

In short, PSPS will never be able to stop all fires from starting and it is impossible to prove success with this protocol because we will never know if electrical equipment would’ve started a fire during the time of the outage. From my observations, it has already not worked on November 8th, 2018 when the Woolsey Fire started from electrical equipment during a time that Southern California Edison had actively been implementing PSPS protocols all week. The Camp Fire also ignited that day and was started by electrical equipment although I’m not sure if that area was being analyzed for PSPS that day or not.

Even with the best analysis available, I believe that it is impossible to know exactly where and when a fire will begin. Wind and weather conditions can shift in an instant. We all know that weather predictions are not all that accurate all the time (sorry NWS friends) and these predictions are what PSPS is solely based around. I also do not believe that shutting off power to massive areas as was conducted by PG&E last week is the solution. So many of these areas never had any fire danger, including the one nearest and dearest to my heart, coastal Humboldt County. My parents had wanted to run their heater because it was actually chilly, cold and plenty humid, with overnight temperatures down to the 40’s in their home a mile from the Pacific Ocean in October. But they couldn’t because their power was off for fire danger. Putting so many people in the dark who are nowhere near the danger zones seems to me to be more of an attention-grabbing political ploy than an actual life safety necessity. I believe that the leadership of California’s investor owned utilities hope that these massive outages will create political pressure to legislate them out of liability for future fires in exchange for keeping the power on.

As evidenced by last week’s outage, PG&E was not prepared for the level of customer service and information needs that their planned outage created. Humboldt County was not on the list of impacted counties until the day before the power outage occurred. The notification process to individual customers was subpar, with many complaints of never receiving the notification. The company’s website crashed and customers were unable to gain information as to whether the outage would impact them. Clearly, there is much work to be done before the company claim to be prepared to undertake such a massive planned outage again.

How can we stop CA wildfires?

While shutting off power may stop electrical equipment driven wildfires from starting, there are other measures that I think would could be bring similar success without such adverse impacts on populations. For one, PG&E should begin by focusing their efforts on updating their infrastructure to upgrade transmission lines and increase grid segmentation so that if they choose to continue with PSPS in the future they will have the capability to be much more targeted. Such incredibly large swaths of land were impacted by last week’s outage and this could have been avoided if they had the capability to segment their grid to focus impacts the way that Southern California Edison and SDG&E do.

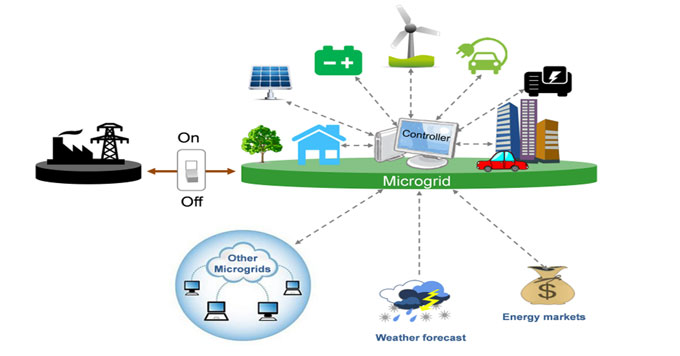

Additionally, the impacts of PSPS could be mitigated by investments in microgrid technology. A microgrid is a localized group of electricity sources that typically operates connected to and synchronous with the traditional centralized grid but can disconnect and maintain operation autonomously. An excellent example of a success story for this type of innovation was revealed in Humboldt County last week when the Blue Lake Rancheria’s microgrid continued to function while the rest of the county went dark. The tribe has been a huge proponent of resiliency planning and has become a leader in tribal emergency management, even bringing FEMA’s emergency management advanced academy to Humboldt earlier this year! During the outage, the tribe’s gas station remained functioning and their facilities provided access to electricity and warmth for local families. The tribe also worked with the Humboldt County Department of Health and Human Services to house eight people who relied on electricity for medical needs in its casino—an outstanding example of an intergovernmental and quasi public-private partnership. In the darkness of PSPS, this mini success shines a light on potential future technology advances that could alleviate hardship.

Unfortunately, it will not be such an easy fix as shutting off power to decrease wildfire frequency. California experienced a prolonged drought from 2011 – 2015 that was the driest since record keeping began in 1885. The amount of dry vegetation in the state’s wildlands coupled with the devastating effects of bark beetles creates a massive amount of fuel that is ripe for burning. Additionally, the state continues to experience record breaking temperatures and an increase in the number of extremely hot days. When humidity dips and high winds commence, massive wildfires are born. While the Cedar Fire of 2003 was California’s largest wildfire for 14 years, the Thomas Fire (2017) only held that title for a mere 8 months before the Mendocino Complex fire overtook it. These disasters are increasing in intensity and frequency due to climate induced conditions. Examining the drivers of climate change and taking action to reduce anthropogenic impacts on the environment is one avenue of working to reduce wildfires.

Another is to reduce further development into the Wildland Urban Interface, the area where suburban developments encroach into traditionally wild environments. California has more people and homes located in the WUI than any other state in the continental US—close to 4.5 million homes and 11 million people. This creates a new type of ignition ready fuel for small brushfires to really take flight. While communities continue to expand outward into the hills and the state faces a housing affordability crisis, policymakers and community developers must consider the price that we will pay when wildfire strikes these areas and reconsider the decisions to continue to infringe on these wild spaces.

Until we are ready to truly address these greater issues, no amount of PSPS will solve California’s wildfire crisis. Is it worth the death of a medical patient dependent on electricity to possibly save the lives and property of many from a wildfire that does not yet exist? While policy makers must grapple with these decisions, California emergency managers must react to the new normal in the wake of devastating climate change induced disasters and rise to this challenge.